Eden, Or Paradise and The Flood

In the Scriptures Eden means an eastern desert country in which YAHWEH planted a garden. Edin, in Sumerian, and edinu in Babylonian, means plain or steppe. In fact in the Scriptural narrative this garden, or Eden, appears as a sort of luxuriant oasis. Garden in Hebrew is gan, and in Greek paradeisos, which the Messianic followers have made into Paradise.Was there a religious tradition by which Abraham could have known of this garden of Paradise? Before answering this question, and to make what follows clearer, remember the three features of the Scriptural Eden.

In the centre there were two trees, clearly distinguished: the tree of life and the tree of knowledge. There was a river divided into four arms which watered the garden. After the sin committed by Adam and Eve YAHWEH posted cherubs to prevent the human couple, who had lost their rights, from returning to the garden. Now we shall find these three elements, somewhat unexpectedly, in Mesopotamian works which are far earlier than Abraham. Some years ago Andre Parrot the Assyriologist discovered the ancient city of Mari, which was sacked by Hammurabi's soldiers in about 1700 B.C. And in the palace of Mari he managed to free from sand an extra ordinary painting known as the 'investiture' which has the following features:

In the middle a god (or a goddess) holding to his chest a vessel from which gushes out a fourfold stream. That is a very ancient Babylonian theme, going back to the third millennium: that is to a period considerably earlier than Abraham's. Obviously we have here the 'four rivers' of the Scriptural description.

On each side of the central feature of the picture are two trees. One of them is too stylized to be identified. The other is a palm tree. We may well consider that these two trees correspond to the two of the Scriptural account.

Lastly, against the trees, and turned towards them, are three weird animals: these are the well-known kerubim, the sacred guardians of Mesopotamian palaces; they are also the cherubs of the Scriptures (Bereshith 3:24).

It is only right to admit that the Mari painting is not in every way identical with the Scriptural description of Eden. Thus the various elements of the picture are duplicated: there are in fact four trees, eight rivers. Archaeologists explain this by the Babylonians' pronounced taste for symmetry, In any case we are bound to acknowledge that in the Mari painting the established Sumero-Akkadian tradition is depicted, and we cannot doubt that Abraham in his day had knowledge, through the handing down of the legend, of the existence of a garden (edinu) planted with mysterious trees, watered by rivers and watched over by winged guardians, the kerubim of the Babylonians.

The Flood

In the first place we must briefly consider the composition of this narrative (Bereshith 6-7). According to Fr Roland de Vaux, O.P., of the Ecole Biblique in Yerusalem, this section contains two parallel accounts: a Yahwistic narrative (J), full of life and colour, and a priestly narrative (P), more definite and thoughtful but also more succinct.6 The final writer respected these two source; received from tradition, which agreed in substance; but he did not seek to get rid of differences of detail. 7On bricks from Mesopotamian libraries archaeologists have been able to make out various accounts of the flood sacred narratives which form the fundamental element of the religious literature of the land of the Two Rivers. At first glance the similarities of these Sumero-Akkadian (and we have even a Sumerian text of very early date) with the story of Noah as it is given in the Scriptures, appears striking enough. But very quickly particular differences (of a spiritual nature) appear, distinguishing the Babylonian versions from the Scriptural account.

Thus the Mesopotamian epic describes a meeting of the gods. After a drunken orgy, for no reason at all they decide to destroy the human race. But one of the deities of this strange pantheon secretly came to warn a man called Uta-napishtim, telling him of the approaching catastrophe and advising him to build a boat on which he will be able to embark with his family and some of the beasts of the fields. At this point the storm occurs, the waters cover the whole of the earth, humanity is wiped out, with the exception of course of Uta-napishtim and his precious cargo.

The gods, much afraid of the terrible destruction they had wrought, took refuge 'in the heaven of Anu, crouching down like dogs', an odd attitude for supernatural beings.

Weeks passed. From a window of the ark Uta napishtim released a dove which at the end of a certain space returned to the ark. A swallow was next released; this too returned. A little later a crow was let out; it did not return and from this it was inferred that it had found a piece of dry land where the floods had subsided. Shortly afterwards the ark touched land. Uta-napishtim then came out of the ark and offered a sacrifice of thanksgiving to the gods, who 'scented the sweet odour (of the burnt meat) and gathered like flies around the altar'.

The imposing Scriptural narrative is quite different in spirit. It shows us YAHWEH, HIS patience exhausted by the wickedness of men and having come to the conclusion that indeed HE can expect nothing of this primitive race which is increasingly plunged in idolatry. As a result HE decides to destroy all, save for one just man, Noah. With this patriarch and his family YAHWEH intends to begin creation over again, on a different basis: justice and mercy, punishment of evil, yeshua granted to men whose hearts have remained pure.

Although the two versions, the Babylonian and the Scriptural, show some curious points of resemblance, the spirit inspiring them could not be more different. In the Mesopotamian account a rather sordid materialism seems to prevail. In that of Bereshith there is an enlightened spirituality in which the principal lessons of applied morality appear.

The old Sumero-Akkadian theme of the Flood formed an integral part of the pagan beliefs seen at Ur to Canaan by the nomad shepherd Abraham. But later, in the course of centuries, at the period of the kings, and especially at that of the Exile, the archaic tradition of the Mesopotamian Flood was most probably revised and recast, to become, on a final analysis, a sort of moral tale. The reader is probably aware that certain Assyriologists pride themselves on having discovered at the site of their excavations very clear traces of the Flood. In Lower Mesopotamia, in those cities in which the archaeologists have undertaken deep excavations, layers of alluvial earth have been discovered which are proof of an extensive flood. And certain specialists have not hesitated to hazard the opinion that we have here proof of the Flood.

It would be better, probably, to talk of floods in the plural; or, better still, of inundations by the river, which occurred locally at successive periods. Of course, as has just been pointed out, in certain cities there can be observed a river of mud now solidified, separating two civilizations of different dates. A catastrophic inundation occurred and life could not continue in these places for a long time after the destructive invasion of the waters of the river.

But the dates of this Flood differ from city to city. And the Flood itself does not seem always to have happened with the same violence. Thus, between the flood of Ur (dated by Sir Leonard Woolley in 2800) and the flood of Kish (dated by Langdon in 3300) there is an interval of 500 years. At Nineveh the Flood occurred about 3800-3700. Further examples could be given: nowhere do the dates agree.

In the present state of our knowledge it would be wise to adopt conclusions like those of Andre Parrot, the Assyriologist: this flood, or rather the floods must be regarded merely as regional inundations due to the breaching of a dyke intended to retain as far as possible the waters of the river. The great variation in thickness of the layers of alluvial mud shows us that in one place the flooding must have been a dreadful tragedy, while in another elsewhere it was merely incidental. Consequently, it is not surprising to find that the dates of the various floods differ very considerably. Finally, it may be added that according to the geologists the overflowing of its banks by the Euphrates was never a generalized phenomenon.

On the other hand, it can be easily understood that these

excessive floodings, often of a terrifying nature, should, with the help of an

oriental imagination, have assumed the appearance of a worldwide catastrophe in

which the whole of human-kind perished, always excepted, of course, the man in

the boat with his family and his cargo of animals.

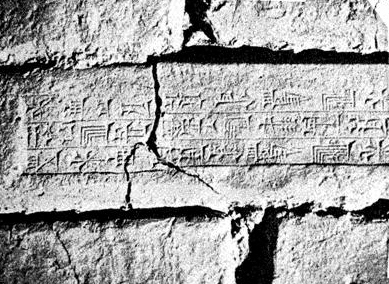

Cuneiform characters

6 The Yahwistic narrative given here by the Scriptures was certainly preceded by several written versions, reproducing oral versions of a much earlier date; it took form and was consigned to writing very probably at the time of King Solomon (970-931), The priestly narrative is nowadays regarded as being drawn u) during the exile in Babylon (586-538); but it only took definitive form after the Return (538).

7 The following differences may be noticed In J the flood lasts forty days and in the ark Noah took in seven pairs of clean animals and one pair of unclean animals, In P the flood lasts 150 days and Noah took with him only one pair each kind 'having the breath of life'.

You are here: Home > History > Abraham Love By YAHWEH > current