Who was Abram?

There are three questions to answer here:

What was the social milieu in which Abram spent many years before leaving Sumeria?To what branch of humanity did his family belong? What was his race?

What exactly was the spirituality and the circumstances which faced Abram as those practiced in the city of the Moon-god until he set out for the land of Canaan?

Abram's social class at Ur

We know the distinctive characteristics of the social system then in vogue at Abram's time in Sumeria. Various legislative and administrative texts discovered by the archaeologists furnish precise information on this subject.The three social classes in Abram's time (in about 1850 B.C.)

Next to the ruler (patesi) , who was the god's representative, at the head of the hierarchy were the patricians or amelu. To this category belonged the court dignitaries, the high officials, the priests and the leaders of the army. Immediately below this privileged class came the mushkenu, the plebeians or free men; they were the merchants, scribes and private individuals practicing liberal professions, landed proprietors and small farmers.The third class was made up of the slaves, the wardum. Among these were included prisoners of war, the children of slaves and sometimes former free men reduced to slavery by reason of debts that they were unable to pay.

With this in mind we can now inquire to which of these three classes the patriarch Abram, a native of Ur and the faithful subject of the Moon-god Nannar-Sin, belonged. The Scriptures tells us nothing about this, but several investigators have tried to provide an answer to the question.

Abram's social class

According to certain theories Abram was quite simply a Chaldean' priest, that is, a wise man who in the peace of a religious atmosphere had assimilated all the knowledge of his times -mathematics, geometry, astronomy, geography, medicine, zoology and botany, philosophy and religion. Abram, then, would have formed one link in the long chain of the initiates trained through meditation on the Symbols and thereby enabled to attain to the heights of 'knowledge'.All this belongs to the realm of fable. If Abram had been a learned man, a real fount of knowledge, or even merely a cultured man, the scribes of later times would not have failed, we may be sure, to record the fact as an important part of the tradition about the 'father of all believers'.

Abram was not a 'Chaldean' priest, well founded in Sumerian science (which was far from being a negligible quantity), nor a Babylonian initiate, well equipped with exotic and esoteric knowledge. Rather he was one of those perpetual wanderers in desert places, a man of open mind and keen intelligence, no doubt, but also, quite certainly, unable to read or to write cuneiform signs on a clay brick.

According to the British archaeologist, Sir Leonard Woolley, Abram, the townsman, left the city of Ur of his own free will. He left one of those houses whose site has been investigated by Woolley himself. In obedience to the orders of Terah, the head of the family, Abram, on this view, together with the whole of his household, left the city-state and set out for the steppe. This would fit in with the end of chapter 11 of Bereshith, which tells us that: Terah ...made them leave Ur of the Chaldeans to go to the land of Canaan (Bereshith 11:31). Woolley's theory follows the Scriptural text scrupulously.

The truth is that it is inconsistent with the laws of human geography: a nomad, sooner or later, is destined to settle down, but it is very unlikely that one who has done so will return to the life of a nomad.

Thus on psychological as well as on historical grounds it is difficult to imagine that Abram suddenly made up his mind purely and simply to desert his house at Ur with its rooms furnished with beds and cushions, his comfortable dwelling, cool in summer and warm in winter, his well-stocked cellar, his fountain of cool fresh water. It is inconceivable that a human being, especially one with a highly developed standard of life, should at one fell swoop reject all that to return to the nomadic civilization of his remote ancestors.

Moreover, even if the idea had entered the heads of Terah and his son Abram, to carry the plan into execution would have imposed great physical strains. To bear the severe conditions of wandering camp life, perpetually putting up and taking down the tents, to endure the exhausting tempo of this existence, a man must be born to it. The women and children, brought up in the city of Ur, would never have been able to survive so arduous an ordeal.

On the other hand, Abram could not have belonged to the official class, the arnelu. In the first place the government would never have allowed his departure, for in the social system of that theocratic state it would have been equivalent to desertion. Add to this the fact that Abram's whole state of mind, which we shall shortly examine, was entirely at variance with a vocation to the life of an official or a warrior.

It is equally impossible to place him among the freed slaves. For how could a man of the slave class have amassed a sufficient sum to buy his freedom, together with that of his family, and become the leader of a pastoral tribe? So far we have only reached negative conclusions; a positive solution must now be attempted.

In the Scriptural text placed at the head of this chapter we are offered absolutely no information about Abram's social class during his time in Sumeria. Subsequently, however, the Old Covenant, by implication, enlightens us on this point. Reading between the lines we observe a human group quite clearly adapted to the very special way of life to be found in nomadism. All the elements of this organization, comprising the leader, the shepherds, women, slaves, assume their very different roles rapidly and effectively. There is never any hitch in the planning of this work, despite its arduous nature. Nor is there any hesitation when an immediate decision is required by the unforeseen demands of life on the steppes or in the desert. Everything is carried out with the characteristic reactions of hardened nomads with a profound knowledge of their occupation and all its finer points, well able to deal with drought or the question of finding fresh pasture for their flocks.

And then it should be noticed that never once in Abram's time, in that of his grandson Yacob, or in the course of the first generations of his family, did any of them experience the least temptation to return to the life of the city. On the contrary, all the patriarchs and the men of their tribe showed considerable repugnance to an urban existence. They give the impression of deep attachment to a long-standing tradition as shepherds. Consequently, when Abram and his father made up their minds to leave Ur, this small human group was not composed of city-dwellers, but of wandering shepherds, always on the move on the steppes. Abram was a wanderer, a nomad and the son of a nomad, whose ancestors for centuries past, possibly for a millennium or longer, had lived in tents. That seems the only conclusion.

Abram a Semite

Abram was a Semite; we have already encountered this term more than once. But such a term is valueless if unaccompanied by adequate explanation, and such an explanation is not always available.Origin and evolution of the term Semite

The Semites, the Scriptures informs us, were the sons of Shem, who was himself the son of Noah.The builder of the ark, it will be remembered, had three sons, Shem, Ham and Japheth. Like all the men of ancient times the Hebrews liked to think that a racial group must have a common ancestor. Thus Shem was regarded as the father of the Semites, Ham of the African peoples, the Canaanites and Egyptians, and Japheth of the men of white race (the Indo-European branch). Modern ethnology considers that the process of. peopling the earth in general, and of the Near East in particular, was a matter of far greater complexity.

The genealogy of Shem is completed as follows. According to Hebrew tradition, amongst his descendants were Aram, Asshur and Eber, who became the 'fathers' of the three Semitic nations the Arameans, the Assyrians and the Hebrews.

Until the end of the eighteenth century this family notion of history was admitted without much discussion. Nevertheless, as the ethnologists, and, principally, the specialists in oriental languages, progressed in their researches it led to a gradual revision of the earlier thesis. And although agreement has not been reached between the various schools of thought it is possible to put forward the explanation which at the present time meets with the largest measure of acceptance.

No such thing as a Semitic race?

Whether we are talking of Indo-Europeans or Semites,of the black or yellow races, it would be futile at the present moment to seek in any country of the world what is customarily called a 'pure' race. Already in remote prehistorical times various human groups, with strongly contrasting characteristics, underwent considerable modification as a result of continual migration and intermarriage. In addition, at the dawn of historical time (about 4000 B.C. for the Near East) in every place only populations of inextricably mixed ancestry are to be found.As a matter of fact the Semites never constituted a distinct ethnic group. In prehistoric times, in northern Arabia we already find groups of wandering shepherds of differing origins and characteristics. They were tribes continually on the move, following their flocks. But, in the end, almost identical geographical and economic needs led these nomadic groups to adopt the same social customs, the same language, and the same ideas of legislation and coercion (lex talionis). Subsequently, there was mutual borrowing from one tribe to another of defensive religious rites and protective deities. By gradual stages all these elements, of very different character, came to present the same cultural appearance. There is, therefore, no Semitic race, but there is a Semitic civilization. Better than a long explanation, diagrams showing the five great Semitic invasions will enable the reader to follow the general progress of these tribes, and, more especially, the path followed by the Aramean group, to which Abram belonged.

Abram's faith at Ur

In the chapter of Bereshith giving the life of Abram no information is given about the belief followed by Terah and his son Abram at the period when they dwelt at Ur in Sumeria. The only information that we have on this subject is to be found in a much later work, the Book of Yahshua Ben Nun: 'In ancient days your ancestors lived beyond the River -such was Terah the father of Abraham and of Nahor -and they served other gods' (Jos. 24:2).Indeed for these wandering shepherds, always in quest of fresh grass and water, the fact of passing from the territory of one city-state to that of another, from the government of one prince to the dominion of a neighbouring patesi had, we may be sure, scarcely any importance. The itinerant Bedouin felt only a relative attachment to the great protective proprietary deity of the country (Nannar at Ur; lanna at Uruk; Utu at Larsa, Enki at Eridu; and so on). They remained more readily attached to the old religious traditions of the former patriarchs of Arabia.

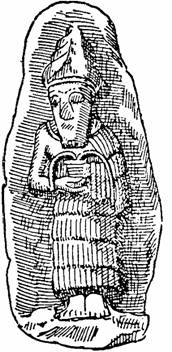

Thus the Semites of the second millennium revered certain gods who were given a marked personality, the sun and the moon, for example. In addition, they devoutly carried with them the teraphim, their little domestic idols; household gods who were the protectors of their families.

On the other hand, worship was paid to certain solitary trees, to caves and to springs, and to certain phenomena in connection with the atmosphere and the soil. All this enables us to understand that, on a final analysis, the authentic religious rites of the primitive peoples consisted not in prayers coming from the heart (a characteristic of religions in an advanced state of development) but in magic; by the help of the practice of sorcery, man, immersed in hostile surroundings, endeavoured to control external and invisible powers.

Such, on the whole, must have been the religious beliefs of those around Abram. It must be added that at the time when the small clan still dwelt 'on the other side of the river' its members looked on death as something different from annihilation. In Sheol, the dead continued to enjoy an existence similar to that which they had led on earth, but one with a slower tempo, and in an atmosphere that was far more dreary, and of course with no question of moral reward.

Finally, Abram must certainly have gone, at least on certain occasions, to the Temenos of Nannar, the Moongod, and saw the deity's subjects, in the sacrifices and obligatory ceremonies. On this account he must have had occasion to pass through some of the streets of the city of Ur, certain aspects of which have been described above. It was in this curious spiritual ground that YAHWEH was soon to plant HIS seed. It was ground ill prepared, it would seem, for the seed to germinate. How would the unenlightened mind of this ignorant Bedouin react to the call of YAHWEH, to the summons of a supernatural being very different from what Abram could have hitherto known and venerated?

Teraphim of Tello.

You are here: Home > History > Abraham Love By YAHWEH > current