CONCLUSION:

SOLOMON AT THE BAR OF HISTORY

We have followed Solomon through his career. But he is too complex a personality to abandon directly he disappears from the scene. To obtain a more accurate idea of a king who is usually presented in a somewhat questionable light it is important, to obtain from the historian a sort of epilogue which will complete, perhaps, one of the most mysterious characters in the chronicles of Yisrael.

Two portraits compared

David, as we know, was an ordinary shepherd of Bethlehem; and Jesse his father was an elder of the village. Too much importance should not be attached to this title, for David, like any farm hand, watched over the flocks of sheep. In the course of years he had grown: immensely wealthy as a result of raids and warlike expeditions; when he became king, therefore, he knew the value of money; he knew from experience what effort was needed, what dangers must be undergone, to acquire it. His peasant origins prompted him to conduct his financial affairs with wise prudence, and he took care to build up large reserves of precious metals.

Solomon, on the other hand, was born to the purple, both figuratively and literally; to that sumptuous Phoenician purple imported straight from the looms of Tyre in which the sons of the king were clothed. He belonged to the generation which found it quite natural to enjoy the advantages of his father's victories.

On his accession we find the young king plunging his hands deep into the gold which formed his inheritance; he appeared always ready to launch out into all sorts of foolish expenditure, even when it was beyond his means. With such methods the royal treasury was soon empty.

It made no difference, he merely squandered more. And to continue his progress on the road to ruin he borrowed from Hiram, a banker who was always ready to give an advance until the day when he required to be repaid by the possession of a part of Yisraelite territory.

A careful father breeds a spendthrift son. David filled the coffers, Solomon emptied them. David worked to enrich the kingdom, Solomon encompassed its ruin.

On every occasion, it could be said, David imposed himself upon us by a sort of personal, almost magnetic charm. In the preceding volume we saw the keen sensibility of this inspired poet whose lyrical effusions remain unequalled models of appeals to YAHWEH or of confident prayer. We saw too that this king possessed a profound sense of justice enlightened and tempered by a sensitive piety. Even his sins do not turn us against him, when from the depths of his soul he so movingly expresses his remorse. As a leader of men, a campaigner, who for the greater part of his life was waging war, he appears to us on a last analysis both as a superman and as a person intensely imbued with humanity.

It was far otherwise with Solomon; a cold, impersonal sovereign who refused to confide in anyone; a chilling personality in his arrogant attitude. David we know as one of our friends; we can see clearly into this childlike soul which is wide open to our gaze and inquiry. But Solomon remains impassive and impenetrable.

With David we encounter a charming simplicity of life. It is true that a great part of his life was spent in a soldier's tent. But when he had achieved fame and fortune and at last could settle on the rock of Yerusalem as a victor, he was careful not to adopt the oriental pomp of the sovereigns of neighbouring countries. His brilliant success never turned his head. Before all else, he desired to remain the king of the People of YAHWEH whose lofty mission it was to proclaim and observe the law of Mosheh.

With Solomon, on the contrary, the state of mind of the upstart prevailed. It was a reign of excesses; he launched out into undertakings that were ruinous. His unfortunate and mistaken outlook prevented his understanding all that he was losing by neglecting his duties as monarch of Yisrael in order to become an oriental potentate.

By simple contrast, the period immediately preceding Solomon's reign furnishes a curious sidelight on his general behaviour. But the long and tragic period of three hundred and fifty years which follows this reign makes plain for us with a far crueler precision the terrible responsibilities of this monarch.

After Solomon Yisrael hastens to its decline

(931 586 B.C.)

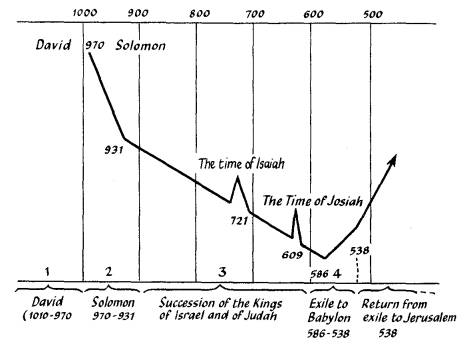

For something like two centuries after the flight of the tribes of Yisrael out of Egypt under Mosheh' leadership (about 1125), Yisrael's spiritual evolution can be shown as an almost continuous ascending curve (see graph). It seemed clear that Yisrael was going forward in great strides towards immense achievements which indeed began to be carried into effect at an increasingly rapid rate.

Then, suddenly, Solomon's baneful activities brought this forward movement to an end, and it seemed as if this would compromise irreparably the existence of the Chosen People.

Indeed it is impossible to form an honest judgment on the reign, at least as a whole, without taking into account the series of great disasters which were the fatal consequence of Solomon's mistakes.

The following tragedy in five acts here rapidly summarized will enable us to form such a judgment.

First Act (931)

Solomon had just died. At once there occurred the separation of the two national parties, Yisrael and Yahudah. The northern group of the ten tribes of Yisrael resumed its freedom in relation to the tribe of Yahudah (flanked by the small group of Simeon) and declared its independence. David's work of unification was destroyed. It was a disastrous political action which was accompanied by a kind of schism; Yahwism, if not cut in two, was at least diminished and its unity threatened.

Second Act (931-740)

Two centuries of fratricidal warfare followed, only occasionally interrupted by a truce. A brief invasion by Egypt. Thus Yisrael and Yahudah needlessly weakened each other.

Third Act (740-721)

The matter was settled rapidly in the course of twenty years. The formidable military power of Assyria appeared in the north of the Middle Eastern theatre. In 724-723 its sovereign Shalmaneser V, besieged Samaria, the capital of the government of Yisrael. In 721 his successor, Sargon II, attacked the city, destroyed and deported to Mesopotamia all its in habitants, and replaced them with settlers from abroad.

The ten tribes of Yisrael (natives of the north) disappeared from history.

Fourth Act (721-605)

A little more than a century of Assyrian occupation.

Fifth and last Act (605-586)

At first, for about ten years, Yerusalem remained under threat from a new enemy, as formidable as its former one; this was the neo-Babylonian dynasty which had just taken the place of Assyria on the battlefields of the east. In 586, Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, stormed Yerusalem the capital of Yahudah, destroyed it utterly together with the Great Tabernacle of YAHWEH, and deported to Babylon the leading inhabitants of Yerusalem.

It looked like the end of the Chosen People.

That is the lamentable picture to be obtained from the history of the Middle East.

Strange formation of the legend of Solomon

Solomon, as has been pointed out on more than one occasion, was a king greatly hated by the majority of his subjects. On the other hand, it will be observed that this same king was extolled by the historians of late: centuries; this may well surprise us, particularly if we are fully aware of the baleful part played by this sovereign.

The explanation is simple: Solomon's legend was gradually built up in the popular imagination during the periods which followed his death. It has just been pointed out that directly after his death the two groups of Yisrael lived through a period of tragic events: Mesopotamian invasions, systematic massacres, merciless deportations. During these terrible trials the People of Yisrael took pleasure in the memory of the long years of peace, the undeniable power, the imposing magnificence of Solomon's times; and those times, as they receded further and further into the past, gradually assumed the qualities of a golden age. Was it not then that the Great Tabernacle of Yerusalem was built, that house of YAHWEH which had now been destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar's soldiers? At that time Yahudah-Yisrael was a rich and powerful nation, treated as an equal with the great sovereigns of the East. These sons of Yacob who thus recalled the memories of a wondrous past had obviously not endured the inhumanity of forced labour. In addition, by common agreement, a veil was drawn over the evil memories of the reign and only the times of honour were recalled. The past was recreated in an optimistic way; people only wished to remember what could be held to the honour of the nation.

Thus century after century the legend of Solomon was gradually built up.

That, indeed, is a fairly common phenomenon in history. In the time of Charlemagne, for example, the peoples of western Europe were worn out by the continual campaigns taking place every spring, either to the east of the Rhine, to the south of the Pyrenees or beyond the Alps. War was unpopular. Yet some centuries afterwards the battles of Charlemagne were celebrated in song throughout the whole of France by apologists who of course had not had to fight. The legend of Napoleon grew up in the same way; at the end of the Empire the forests and mountain fastnesses had become refugees for those endeavouring to avoid conscription, for the French were growing tired of the constant slaughter of their sons. But once Napoleon was dead we discover that the military history of those years had become a legend and was related with little regard for the harsh realities of what actually occurred; it was only the stirring events which were remembered,

All epics, in fact, are only a freely interpreted account of certain periods of national history.

It is in this way that in Solomon's case the strange manner of his legendary rehabilitation is to be explained; it occurred through the rather moving efforts of people in the throes of misfortune endeavouring to survive by the memories of a past that undeniably had been touched up for the needs of a cause.

Solomon's defenders, nevertheless, can plead extenuating circumstances. It must be agreed in the first place that the two Scriptural writers -the authors of the Books of Melechim and Divre Hayamim -were very largely responsible for the favourable judgment passed by posterity on Solomon's government and conduct. The documents on which these authors relied belonged to the Priestly tradition and so we cannot be surprised at the fact that they heap praises on the builder of Yahweh's Great Tabernacle, and passed lightly over the more sombre side of the reign.

On the other hand, in these circumstances many readers in ancient times had every excuse for regarding Solomon as one of the best kings of Yisrael.

And then, it must be emphasized at once, Solomon’s whole work remained in existence right up to his death. A superficial observer would have grounds for coming to the conclusion that the king had built on solid foundations, that his achievements were indestructible If after his death a general collapse occurred it might after all, be the responsibility of the blunders or incapacity of Solomon's successors.

Was Solomon's achievement really based on solid foundations? By no means. In the last years of his life it was at the point of collapse. It might be compared to those African houses in which all the beams, the walls and furniture have been hollowed out by the slow, invisible work of a colony of ants and which collapse in a cloud of dust at the slightest touch.

With Solomon, right up to the last minute we remain in the disturbing world of camouflage where reality is masked. But the prophets -they appear on the scene and are dealt with in the next volume -were not deceived; they had no hesitation in passing judgment of merciless severity on Solomon; they thundered against his sins and his criminal improvidence.

THE SPIRITUAL DECADENCE AND SPIRITUAL REVIVAL OF THE PEOPLE OF YISRAEL

1.1010-970 Reign of David.

2. 970-931 Reign of Solomon. Financial, religious, political, social and moral failure.

3. 931-586 Political collapse of the Chosen People. Also their spiritual collapse despite the warnings of the prophets. Foreign invasions, national catastrophes. 721:disappearance of the Ten Tribes of Yisrael, 586:destruction of the Great Tabernacle of Yerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon.

4. 586-538 Captivity in Babylon, where in their terrible misfortune the elite of Yahudah rediscovered the exact meaning of their spiritual mission.

538 Return of the exiles to Yerusalem. Continuation of the spiritual revival, already begun in Babylon, which makes progress and causes the curve to ascend.

Period 2 is dealt with in this book.

Periods 3 and 4 form the subject of the next volume in this series.

To link this graph with the preceding one see graph.

'My kingdom is not of this world'

We have just traced the somewhat confused course of events which in three and a half centuries has brought us to one of the greatest tragedies ever experienced by the Chosen People; it led to the disappearance of the ten tribes of Yisrael, the sacking and destruction of the Great Tabernacle of Yerusalem, and the exile of the leading citizens of Yahudah in Babylon. Politically, the catastrophe was practically complete.

But at the darkest, most agonizing moment, unexpectedly there came the promise of a triumphant era, unprecedented in the world of spiritual thought and experience.

With Solomon we are plunged in a period of stupidly materialistic messianism; this implied the awaiting of a envoy from YAHWEH who would ensure the complete definitive triumph of Yahwism, through the agency the Chosen People who would dominate the world. It was the task of Solomon and his successors to prepare the way for this Messiah, who one day would establish the reign of YAHWEH over the Earth.

It is not by political power, by the establishment of a chariot force, by splendid architectural achievements by a dazzling sacrificial liturgy that we are to work for the coming of the Ruwach. Quite plainly, Solomon's ideal set off in the wrong direction; it is hardly surprising that it finally came to a dead end.

At the earliest moment Yisrael had to return to the right road. For this purpose it had to be stripped (by the grasping hands of the Egyptians and Babylonians) of external riches. It had to rediscover those spiritual riches which the prophets began to reveal. To return to the right road, Yahudah, the only survivor of the family of Yacob, had to take a long detour on their spiritual path by way of Babylon, where the moral sufferings of the captivity awaited them. But in misfortune the sons of Yisrael wrought for themselves a new soul.

Yet even at that stage in their progress towards YAHWEH, five hundred years were needed before they were ready to receive the Master's saying: 'MY ,kingdom is not of this world.' The theology of King Solomon's period could not even begin to conceive such a possibility.

Back Solomon The Magnificent Next

Solomon The Magnificent Index Solomon Sitemap Scripture History Through the Ages Solomon The Historian RADIANT DAWN Solomon's Wisdom SOLOMON IN ALL HIS HONOR David's role in building the Temple Dates of the building of the Temple Division of the Temple The Ark of the Covenant The most Kodesh Place Dedication of the Temple SOLOMON Prince of Peace SOLOMON THE TRADER Solomon's Ophir expedition The queen of Sheba LITERARY ACHIEVEMENTS OF SOLOMON First historical works of the Hebrews What did Solomon write THE SHADES OF NIGHT Political and social failure Solomon's spiritual failure The moral failure of Solomon CONCLUSION of Solomon