Details Of The Mohar

Mesopotamian law fixed the amount of the Mohar (dowry, purchase price for wife) at fifty shekels of silver.12 But in certain cases payment in precious metal could be replaced by giving service, a practice which some historians regard as a more ancient institution than paying for a wife. In this case the young man offered to work for his father-in-law to be (or his legal representative) for nothing, so that at the end of the contract of service he could obtain the bride he desired.

'I will work for you seven years to win your younger daughter Rachel,' said Yacob. The bargain pleased Laban, and he replied: 'It is better for me to give her to you than to a stranger; stay with me.'

12 Cf. Devarim 22:29 the man who is convicted of seducing a young woman who is not yet betrothed must give the girl's father fifty silver shekels. There is an almost identical provision in Shemoth 22:15. The exact equivalent weight of a shekel is disputed. The Jerusalem Scriptures estimates it as 0.39 ozs or 0.0114 kilograms.

.

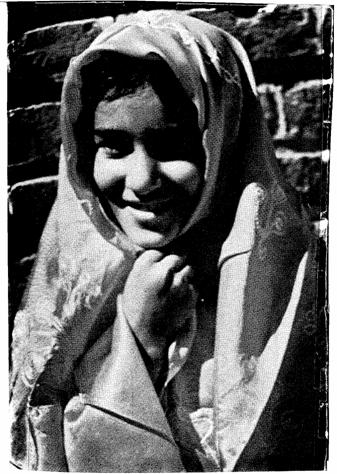

Rachel must have looked like this.

The Hard Life Of An Oriental Shepherd

It was certainly no sinecure (a salaried position requiring little or no work) looking after large flocks of sheep and goats in the open country of the Near East. As a rule the grass was thin and cropped short. As they went along the beasts grazed; from morning to night they lost not one minute, as they went slowly forward over the grass. Great expanses of pasture were consequently needed and those in charge of the flocks had to keep at a certain distance from each other. The shepherd of each flock was thus condemned to almost complete solitude. It was only in the evening at the local well that men were together for a short time.

Throughout the day watch could not be relaxed for a moment. If an animal wandered away, it had to be found and brought back; if one fell in a ravine it had to be pulled out. A sheep broke a leg, another was sick; the shepherd had to turn himself into bonesetter or veterinary surgeon. At lambing time there were innumerable duties to perform in caring for the ewes.

When night fell they had to be even more watchful: wolves, foxes, bears, even lions in certain parts, would prowl round the sleeping flocks. With the help of half-wild watchdogs the shepherd made continual rounds of the flocks and it was by no means rare for him to have to fight off the marauders. And then there were the human thieves as well who were certainly no less formidable.

The animals entrusted to the shepherd's care were counted and he remained responsible for them to his master. Both Sumerian and Semitic legislation agreed on this point. 'If a lion kills a beast in a sheepfold,' the Code of Hammurabi lays down, 'the owner of the sheepfold shall be responsible for the damage,' in other words, the shepherd was exonerated. The Hebrew law contains the following prescriptions: 'If the animal has been stolen from him [the shepherd], he must make restitution to the owner. If it has been savaged by wild beasts, he must bring the savaged remains of the animal as evidence, and he shall not be obliged to give compensation.'

One day when argument between Laban and Yacob grew heated the latter enumerated his grievances. He gave a graphic account of his activities which enables us to obtain a fairly close idea of his hard life as a shepherd. 'Your ewes and your she-goats have not miscarried' [an expressive way of emphasizing that they had received all necessary care at lambing or kidding] 'and I have eaten none of the rams from your flock. As for those mauled by wild beasts, I have never brought them back' [the legislative texts quoted above stated that the shepherd had the right to show proof of the fact and was thus freed from responsibility to make good the loss], 'but have borne the loss myself; you claimed them from me, whether I was robbed by day or robbed by night' [Here the argument was specious: with thefts in the proper sense of the term it was the shepherd's responsibility to track down the thieves or prevent them; he was responsible for everything that he allowed to be stolen.] 'In the daytime the heat has consumed me, and at night the cold has gnawed me, and sleep has fled from my eyes. YAHWEH has seen my weariness and the work done by my hands.' Seven years of this hard life had been Yacob's, but he was working to win Rachel. And these seven years, Bereshith tells us poetically, seemed to him like a few days because he loved her so much.

Set A Thief To Catch A Thief

Yacob was now in a position to claim his wages from Laban; by his work he had paid off in some sort the dowry required of the bridegroom. 'My time is finished,' he told his uncle. It was a splendid wedding. There was no spiritual ceremony at all at the time of the patriarchs. The chieftains of the neighbouring clans were invited for the celebrations and the banqueting continued for a whole week. On the first night the young wife, duly veiled, was taken to her husband's tent. All this followed the rites of the nomadic Semites.

Hitherto, Yacob seems to have acted on the principle of tricking others, but in uncle Laban he appears to have found one more cunning than himself. On the morning after the first wedding night, at daybreak, Yacob was astounded to find that it was not his beloved Rachel who had been brought into him but her elder sister Leah. The previous evening the veil covering her face had enabled Laban to play this trick, but at first light Yacob discovered how he had been made a fool of. There followed a stormy scene with his uncle. 'What is this you have done to me?' demanded Yacob. 'Did I not work for you to win Rachel? Why then have you tricked me?'

In an argument Laban could hold his own with anyone. 'It is not the custom in our country,' he replied, 'to give the younger daughter before the elder.' And he went on to offer Yacob another arrangement: 'Finish this marriage week and I will give you the other one too in return for your working with me another seven years.' The bargain was concluded on the spot.

Laban had already given Leah a slave-girl named Zilpah. To Rachel on her wedding day he gave a slavegirl whose name was Bilhah. Both slaves were destined to play an important part in the development of the genealogical tree of Yisrael, since they soon became, quite legally, Yacob's concubines. Two wives and two concubines. Now Yacob loved Rachel more than Leah. We know what to expect. One master with four wives, one of whom was the favourite. Trouble was obviously looming.

Yacob Called Yisrael Index Yacob Sitemap Scripture History Through the Ages Yacob Called Yisrael Yacob and Esau Theft Of The Paternal Blessing Flight, The Only Solution For Yacob Yacob's Dream At Bethel Yacob Puts Up A Stele Named BethEl The Location Of Bethel Importance Of The Well, A Meeting Place Details Of The Mohar The Sons Of Yacob How Yacob Became Rich Yacob Leaves The Land Of The Fathers Treaty Between Yacob And Laban Messages Between Yacob And Esau Yacob Wrestles With YAHWEH Two Brothers, Yacob and Esau Meet Towards The Promised Land The Departure From Shechem The Conclusion Of Yacob