MARCHES AND COUNTER-MARCHES

The valley of death and the fiery serpents

Mosheh remains in the wilderness until the unwarlike generation was dead

Mosheh seems to have been well aware of the mediocre quality, to say the least, of his army. His men thought only of returning to Egypt to continue their lives there as stock-breeders and farmers. They forgot about the forced labour and thought only of going back to the gardens on the banks of the Nile. Mosheh’ plan remained very simple and realistic; for the time being they were to remain in the wilderness until the unwarlike generation was dead, for with them there could be no question of attempting the conquest of Canaan. In addition, of course, the youthful members of the tribes needed to prepare for the SET APART war awaiting them. They were continually reminded that this land was theirs; YAHWEH had promised it to them on oath; they could and ought to consider it as their property. Yisrael’s lawgiver assured them of their coming victory over its inhabitants. Under these conditions they were eager to rush into battle for it, for this land in which flowed milk and honey soon came to appear to them as their prize and a far more attractive place to live than the plains of Sinai where they moved from one camp to another.

Gradually a strange revolution occurred in the mental attitude of the Yisraelites. While those of them who had been led out of Egypt by Mosheh looked forward to returning to their peaceful existence in their tents on the Delta, the younger generations were eager for battle. These nomad shepherds could already imagine themselves established as settled residents, and, of course, as the masters in the land of the patriarchs.

That does not mean, of course, that as they moved about Mosheh did not encounter serious difficulties with these capricious people. It is true, nonetheless, that on the matter of war their whole spirit had changed. Mosheh had now at his disposal a force that enabled him to envisage going over to the offensive.

Kadesh was a long and distressing experience. But the arduous life as shepherds had put the Yisraelites in fighting trim. And Mosheh, for his part, with his theology, the rules of morality that he laid down and the customary law which he was continually enacting, succeeded in endowing Yisrael with a national spirit. The time for action was drawing near. The question remained, however, at what point were they to make contact with the enemy?

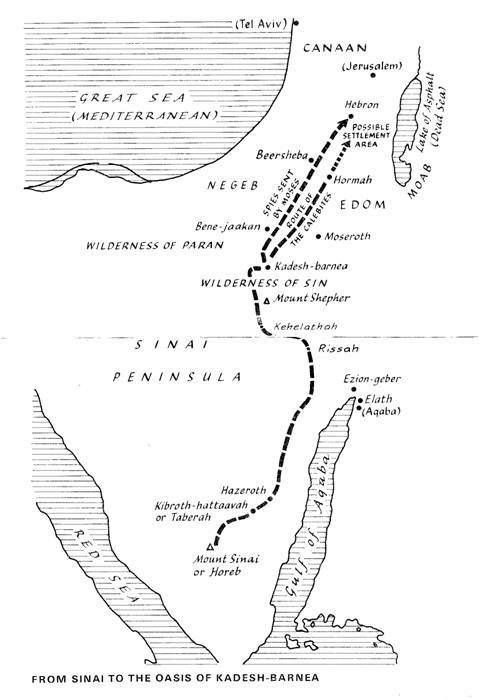

Logically, it seemed obvious that they should march straight north towards Beersheba which was hardly fifty miles distant from Kadesh. Mosheh seems to have decided against this course. His decision can easily be explained. At this period Rameses III sent out expeditions from time to time to disperse the waves of the invading Peoples of the Sea; it is easy to understand, therefore, that Mosheh was not anxious to take this route of the Philistines for fear of meeting contingents of Egyptians.

Edom refuses right of way to Yisrael (Devarim 11:3, Bemidbar 20:14-21; 33:37)

The Yisraelites could also reach the land of Canaan by crossing Mount Seir to the south-west of the Dead Sea; Seir was in the territory of Edom. At the time of Mosheh, the Edomites, Esau’s descendants, were still feeding their flocks in this rather wild country in which, nevertheless, they had managed to cultivate some of the land. YAHWEH had formally forbidden Mosheh to attack this sister people; he therefore sent ambassadors to the king of Edom asking permission to pass through his land. ‘We will not cross any fields or vineyards,’ the Yisraelite delegation explained. ‘We will not drink any water from the wells; we will keep to the king’s highway without turning to the right or left until we are clear of your frontiers’ (that is, until reaching Canaan). ‘You shall not pass through my country,’ replied the king of Edom. Mosheh insisted: ‘We will keep to the high road; if we use any of your water for myself and my cattle, I will pay for it.’ It was useless. ‘You shall not pass,’ reiterated the king.

While these negotiations were going on the Yisraelites had begun to move north-west straight towards Edom. They established their camp at Moseroth, not far from Mount Hor, where a dramatic incident took place. At YAHWEH’s command, Mosheh, with Aaron and Eleazar, the elder of Aaron’s two remaining sons, took the path up the mountain; for as a punishment for his mysterious sin, mentioned above, Aaron was not to enter the Promised land but to leave his bones in the desert. There, on the mountain, Mosheh stripped Aaron of his ritual vestments and vested Eleazar in them; he it was who now became the high-kohen of Yisrael. After this strange ceremony Aaron died there on top of the mountain. For a whole month the Yisraelites wept for Aaron.

The important part of the narrative is the request made by Yisrael to Edom and the unbrotherly refusal of the Edomites. It is hardly surprising if, subsequently, at the time of the Judges and the Kings, they were regarded by the Yisraelites as enemies to be treated without any consideration at all. Or possibly the later enmity between Edom and Yisrael has been incorporated by the storytellers into the epic of the journey through the wilderness. The Edomites assisted the Babylonians when they destroyed Jerusalem.

As a result of the Edomites refusal the Yisraelites turned their backs on the Promised land and set off south. They halted at Bene-jaakan, then went on by way of Hashmonah and Kadesh. After a further halt at Hor-haggidgad they set out again straight towards Ezion-geber near the extreme point of the Gulf of Aqaba, an extension of the Sea of Reeds (see map above). In this way they avoided the land of Edom. They went back up the terrible valley of Arabah in an attempt to reach the borders of Canaan by passing round the eastern end of the Dead Sea.

Arabah is a forlorn region, an absolute wilderness, a real valley of death; parts of it are covered by drifting sand and others consist of vast stony expanses. The Yisraelites advanced over this wilderness in which there were scarcely any wells. Progress became extremely difficult and the people, who did not understand very clearly the political and strategic reasons for all these marches and counter-marches, began to show their impatience, their discontent and, finally, their anger. The Scriptural writer, with his theological outlook, explained the poisonous snakes, from which the Yisraelites suffered, as a punishment. These snakes were probably horned vipers which are very dangerous and abound in this unfriendly country.

It appears that in the circumstances the oriental imagination likened these ‘fiery serpents’ to the winged dragons of Assyrian mythology and Semitic legend. In any case the people, imbued with fear, asked Mosheh to make them a talisman to protect them and to cure them from the bite of the snakes. ‘Make us a fiery serpent,’ implored the crowd, and put it on a standard [in fact, a sort of pole]. If anyone is bitten and looks at it he shall live. Rather surprisingly Mosheh granted their request; he ordered the famous saraph or bronze serpent 1 to be made and it now accompanied the caravan. At the end of this long and desolate gorge the Yisraelites emerged on the frontiers of Moab.

1 Later on this strange emblem was placed in the Temple at Jerusalem. During the campaign against idols Hezekiah, king of Judah (716-688), who broke the Canaanite steles and tore down the sacred poles on the ‘high places’, smashed the bronze serpent (2 Melechim 18: 4) although it was regarded as being ‘made by Mosheh’.

FROM KADESH TO TRANSJORDANIA

The route followed by Mosheh to avoid the territories of Edom and Moab which refused right of way to the Yisraelites journeying to the Promised Land.

Back Mosheh and Yahshua Ben Nun Index Next

Mosheh and Yahshua Ben Nun Founders of the Nation Scripture History Through the Ages